[Note: If you landed here looking for Mastodon- or Fediverse-related resources, there is now a page dedicated to administering Mastodon instances, though very much a work in progress. This post will also be updated shortly, but as it stands, should serve as an introduction to many of the relevant issues.]

I recently responded to this broad, open-ended question on Quora: “What are some ways to prevent and/or deal with legal issues that arise from actions of users on user generated content websites?” Given that I spent five years at MySpace and eHarmony dealing with a panoply of those very issues, I decided to swing for the fence in answering that one. You can read the original answer on Quora, but I decided it was worth posting a beefed-up version here at Techlexica with some additional background covering the bases on fraud, abuse, and similar social media trust and safety challenges.

As background, in the late 2000s, cross-functional risk/abuse teams, now commonly known as Trust and Safety (T&S), grew out of necessity as social media and commerce exploded in popularity. As dominant platforms scaled by orders of magnitude to hundreds of millions or even billions of users, the challenges of the full range of human character and (mis)conduct — exacerbated by the relative anonymity and distance of the global Internet — made for unintended consequences and unprecedented threats at every turn. T&S lies at the intersection between legal, compliance, customer relations, community management/moderation, content review, editorial policy, privacy (“data protection” in EU parlance), and data security. In a nutshell, TSPA defines trust & safety as “the global community of professionals who develop and enforce principles and policies that define acceptable behavior and content online.” (More on conduct vs. content below.)

Site owners in a hurry may wish to skip the commentary and jump to the TL;DR list of practical tips below. As always, as my friends at the Social Media Club like to say, “If you get it, share it!”

Social media trust & safety: Policing the fastest-growing boomtowns in the virtual Wild West

Broadly speaking, from the site owner’s perspective, as the headline reads, if you build it, they will abuse it. That’s actually not quite true; if you build it, and they come — i.e., users visit in significant numbers and keep coming back, some will abuse it.  Whether it’s spammers hawking Canadian pharmacy deals, pedophiles, identity thieves or Nigerian money transfer scammers, those wearing black hats are all too familiar with the strategy of going fishing — or phishing, as the case may be — where the fish are. (At eHarmony, one of our engineers joked that we should consider it a compliment of sorts the first time we got phished; stealing someone’s online dating password doesn’t exactly rank up there with getting access to their bank account.) Put differently, as Willie Sutton apocryphally said, he robbed banks “because that’s where the money is.”

Whether it’s spammers hawking Canadian pharmacy deals, pedophiles, identity thieves or Nigerian money transfer scammers, those wearing black hats are all too familiar with the strategy of going fishing — or phishing, as the case may be — where the fish are. (At eHarmony, one of our engineers joked that we should consider it a compliment of sorts the first time we got phished; stealing someone’s online dating password doesn’t exactly rank up there with getting access to their bank account.) Put differently, as Willie Sutton apocryphally said, he robbed banks “because that’s where the money is.”

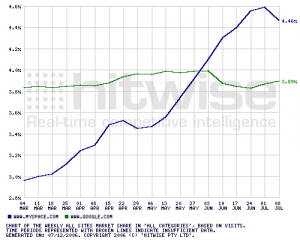

We learned this the hard way at MySpace around 2005, when the site exploded in popularity among teens and young adults — at one point adding more than a quarter million new users per day. (Facebook was still limiting itself to the college market at the time.) It was an overnight cultural phenomenon among people aged roughly 12-25, to which everyone over 40 was completely oblivious, including parents, teachers, police and prosecutors. Tragically, it didn’t take long for the fishermen to figure out where the largest school of fish in history had gathered.

To be candid, an open, profile-based social media site like MySpace can be a predator’s dream. Drawing on the natural traits of exhibitionism, narcissism and voyeurism that blossom in adolescence, the site was brilliantly designed to empower young people to display their individuality online to the whole world as simply, flexibly and frictionlessly as possible, sharing every detail of their daily lives, friends, interests and passions.

Not surprisingly, young people jumped at the opportunity to do just that, to the tune of more than 1.5 billion page views per day — roughly 17,000 per second — with 2.3 million concurrent users. To grasp the size of that virtual crowd, picture a stadium the size of the Rose Bowl, packed to capacity — 25 times over. (At one point, our CTO, Aber Whitcomb, told me we had to unbox, install and provision eight or 10 new servers every day to keep up with growth. This was before AWS came along, of course.) To a high schooler, MySpace became the online equivalent of wearing band T-shirts to school the day after a concert, decorating a locker with pictures and bumper stickers, and plastering bedroom walls with posters of idols and sex symbols — but open to the entire world. By design, the site encouraged openness on profile pages while prudently withholding personally identifiable information (“PII”) for reasons of privacy and safety. (Contrast this with Facebook’s open-book approach, reflecting its roots as a college “facebook” where any student can look up another’s phone number, class year, residence hall, etc.) On MySpace, or any of the major dating sites for that matter, a user might show up as “Sarah from Santa Monica,” without divulging her last name, phone number, address, or even email address; the built-in private messaging system lets members chat about shared interests, flirt, and take things further by exchanging numbers or email addresses if they ever get to that point. If things get ugly or uncomfortable, ties can be severed with a mouse click.

On the criminal side, the same creep could always hang out at malls or playgrounds, but an online profile gives him a trove of source material to start a conversation, feign shared interests or values, and earn the victim’s trust.

More about online safety another time; let’s revisit the original Quora question. Recognizing that most sites will never amass 200 million registered users like MySpace, or 500 million like Facebook, the literal answer is that the most effective way to prevent or deal with legal and risk issues on UGC sites is to minimize the number of users. Simple, right?

All kidding aside, my point is that all of these issues will scale along with site traffic, often exponentially as you become a large enough site to hit the radar screens of bad guys.  In the typical lifecycle of a social Web startup, nobody has a job title that sounds like anything to do with risk or abuse at the beginning; the closest might be a community manager who covers abuse issues as part of keeping the peace in general on the site. As a completely made-up statistic, assume that 0.01% of users are sociopaths or predators who cause serious damage to the community and its other members. With 10,000 users, that’s one guy. With a million, it’s a hundred people. With 100 million registered users — the scale at MySpace when I left — it’s ten thousand. That kind of math illustrates why every major platform has a social media “trust & safety” team that serves as the first line of defense against all kinds of ugliness that may not have legal implications, but can reflect on the character and perceived value of the site. The most serious of these get escalated to Legal; cease-and-desist letters are sent; police, IC3, NCMEC or other authorities are notified; and so forth.

In the typical lifecycle of a social Web startup, nobody has a job title that sounds like anything to do with risk or abuse at the beginning; the closest might be a community manager who covers abuse issues as part of keeping the peace in general on the site. As a completely made-up statistic, assume that 0.01% of users are sociopaths or predators who cause serious damage to the community and its other members. With 10,000 users, that’s one guy. With a million, it’s a hundred people. With 100 million registered users — the scale at MySpace when I left — it’s ten thousand. That kind of math illustrates why every major platform has a social media “trust & safety” team that serves as the first line of defense against all kinds of ugliness that may not have legal implications, but can reflect on the character and perceived value of the site. The most serious of these get escalated to Legal; cease-and-desist letters are sent; police, IC3, NCMEC or other authorities are notified; and so forth.

Most nascent consumer Internet sites and apps will be lucky ever to get to the size where they need to build a dedicated social media trust & safety team, so for the typical founder who wears many hats and does a lot with very little, let’s dive in:

Practical Tips for Social Platform Operators

- Work with the right lawyer who knows his or her way around these issues. There is no substitute for professional advice. An hour or two initial orientation on the full range of potential issues from someone who’s “been there, done that” will easily pay for itself, and with respect to any discrete issue, a five-minute call or email exchange can save you endless headaches.

- It all starts with the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Again, no substitute for having an experienced Internet product lawyer draft/review those, tailored to the specifics of your site. Often you want Community Guidelines as well that dovetail with the TOU, written in plain English, posted somewhere users might actually read them (as opposed to the TOU and PP, which go largely unread on most sites). For a good example, see Gogobot’s guidelines.

- Broadly speaking, there are two main areas of social media trust & safety risk: Inappropriate content and inappropriate conduct among users. For either, the single most powerful point of leverage you have is prevention by self-policing — including a “Report as Inappropriate” link for every post, encouraging users to serve as your eyes and ears, and appointing the most active and responsible users of the site as moderators, admins or “super-admins” who may have the ability to delete posts or even suspend users, depending on how much you trust them. The benefit of this approach is that it’s preventive, scalable, and nearly costless.

- In the taxonomy of inappropriate content, think about spam, phishing attempts, porn, hate speech, and commercial self-promotion (including affiliate links, etc.) as well as the usual trolling, flame wars and personal attacks. The right TOU and Guidelines give you the legal right to delete posts and terminate user accounts at any time for behaving badly in any of these ways. Nevertheless, it’s usually impossible to prevent a determined jackass from coming back again and again, using new accounts and proxy servers as necessary to get around deletions, bans and IP address blocks. In that situation, if the jackass is unpopular, your best defense is to appeal to users to immediately flag every one of his/her posts for deletion, and have your community manager prioritize responding accordingly. (You could pre-moderate every post, but that’s impractical for successful sites with thousands of posts per day or more.)

- Copyright infringement is its own peculiar form of inappropriate content.

There are endless ways users can find to infringe the IP rights of third parties on your site, by posting photos, articles, audio or video clips, etc. Fortunately, you as site operator are generally shielded from any liability provided that you correctly implement a notice-and-takedown policy under Section 512 of the DMCA. There are many resources around the Web explaining how to do that (I like Chilling Effects in particular), but as usual, it’s best to work with a qualified lawyer to ensure you’re covered. Correctly implemented, the DMCA “safe harbor” gives the site operator complete immunity against suits by content owners. (The Viacom v. YouTube lawsuit was a high-profile challenge to this safe harbor, and Viacom lost.) Two traps for the unwary: Be certain to file the form with the U.S. Copyright Office designating a Copyright Agent to receive DMCA takedown notices, and include a street address (not just an email) to which the notices can be sent.

There are endless ways users can find to infringe the IP rights of third parties on your site, by posting photos, articles, audio or video clips, etc. Fortunately, you as site operator are generally shielded from any liability provided that you correctly implement a notice-and-takedown policy under Section 512 of the DMCA. There are many resources around the Web explaining how to do that (I like Chilling Effects in particular), but as usual, it’s best to work with a qualified lawyer to ensure you’re covered. Correctly implemented, the DMCA “safe harbor” gives the site operator complete immunity against suits by content owners. (The Viacom v. YouTube lawsuit was a high-profile challenge to this safe harbor, and Viacom lost.) Two traps for the unwary: Be certain to file the form with the U.S. Copyright Office designating a Copyright Agent to receive DMCA takedown notices, and include a street address (not just an email) to which the notices can be sent. - I could write another whole blog post on copyright issues, but the bottom line is that you don’t have an obligation to independently review every piece of content — but you do have a duty to respond to DMCA take-down requests, if properly made, within a “reasonable time” (usually a few days). The Fair Use doctrine allows much copyrighted work to be used on your site with impunity, but practically speaking, you don’t want to have to be the judge of that — so when a content owner sends a proper DMCA take-down notice, I wouldn’t mess around: Just take the content down.

- Trademark infringement is theoretically an issue, but in practice it rarely comes up. Trademarks are brand names, slogans, taglines or logos. The Web makes it easier than ever to cut and paste them just about anywhere. (Picture something like the Nike swoosh.)

In practice, most of the time brand owners don’t go around threatening to sue UGC sites over trademark issues because it’s generally either a non-commercial use (e.g., a fan expressing enthusiasm), a parody (fair use), a comparison against other products (“nominative use“) — or even if technically infringing, it serves to give the brand more visibility, so it would do more harm than good for the brand owner to send a nasty cease-and-desist letter. However, if you do find yourself on the receiving end of one of those letters, the low-risk approach is to go ahead and remove the content (without admitting liability). If it’s a hugely popular item on your site, it’s worth consulting a lawyer to see if you want to push back and make fair use arguments, etc., but keep in mind that defending even a meritless suit can be expensive.

In practice, most of the time brand owners don’t go around threatening to sue UGC sites over trademark issues because it’s generally either a non-commercial use (e.g., a fan expressing enthusiasm), a parody (fair use), a comparison against other products (“nominative use“) — or even if technically infringing, it serves to give the brand more visibility, so it would do more harm than good for the brand owner to send a nasty cease-and-desist letter. However, if you do find yourself on the receiving end of one of those letters, the low-risk approach is to go ahead and remove the content (without admitting liability). If it’s a hugely popular item on your site, it’s worth consulting a lawyer to see if you want to push back and make fair use arguments, etc., but keep in mind that defending even a meritless suit can be expensive. - Photos and videos pose their own unique set of problems. The main issue there, of course, is nudity or pornography. Every site can set its own standards regarding nudity; whatever lines you draw will be tested and violated. If you decide to allow nudity, make a serious effort to keep users under 18 off the site. Local laws vary and you don’t want to have to defend against some conservative state AG charging you with distributing porn to minors. Ideally it’s best to have someone review and moderate every photo, but in practice, given scalability issues, you may need to rely on a user reporting system for objectionable photos. A special case is child sexual abuse material (CSAM); unlike almost every other US law in existence, businesses have a legal obligation to report an apparent crime to NCMEC if any CSAM is discovered.

- Porn isn’t the only reason to pick a minimum age for access to your site and enforce it. In particular, in the US, COPPA (the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) prohibits the collection of any personal information from children under age 13 without their parents’ consent. This includes things as simple as email addresses. If your non-child-targeted site is of a nature that you know will appeal to kids, your TOU should forbid users under age 13 from accessing the site; the registration process should ask for age or date of birth somewhere to confirm you aren’t registering people under 13; and there should be a mechanism to cookie the user’s browser so a 12-year-old can’t just hit the “back” button and enter a new, higher age. Xanga got in big trouble for this and was fined $1 million by the FTC. (No, not Zynga — Xanga.)

- You are generally not liable for any other unlawful content posted by users on the site, thanks to a wonderful law called Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. (The part of the law that survived Supreme Court review has nothing to do with decency in communications, but the name stuck.) This would cover things like defamation, hate speech, stating discriminatory preferences in hiring or housing, etc. Of course you can and should delete posts and kick people off the site for posting such content (in accordance with those Community Guidelines and TOU), but that should be the end of it. Exercising judgment in deciding which posts to remove does not make the site responsible in any way for the ones that remain.

- Defamation tends to be the most common type of claim that falls within the Section 230 safe harbor, particularly on rating/review sites where it relates to businesses (e.g., negative reviews on Yelp) or individuals’ standing in the professional community (as in Avvo or Honestly.com — see TechCrunch: “Unvarnished: A Clean, Well-Lighted Place for Defamation“).

If someone threatens to sue your site based on allegedly false negative statements posted by a user, it may be necessary to have your lawyer send a nasty letter basically saying “Go to hell, you don’t have a case against the site, here’s why, and if you sue us, we’ll countersue to make you pay our own expensive lawyers’ fees.” I call this the “smackdown letter” and have always found it to be effective. Taking the high road, if the complainant is being reasonable, I always encourage them to post a thoughtful rebuttal to criticism, and/or ask their other, more satisfied customers to post on the site to dilute the impact of the negative review.

If someone threatens to sue your site based on allegedly false negative statements posted by a user, it may be necessary to have your lawyer send a nasty letter basically saying “Go to hell, you don’t have a case against the site, here’s why, and if you sue us, we’ll countersue to make you pay our own expensive lawyers’ fees.” I call this the “smackdown letter” and have always found it to be effective. Taking the high road, if the complainant is being reasonable, I always encourage them to post a thoughtful rebuttal to criticism, and/or ask their other, more satisfied customers to post on the site to dilute the impact of the negative review. - Unlawful conduct (as opposed to content) is usually less of a problem on UGC sites for the simple reason that most of it either happens offline or in other communication channels away from your site. In a social media trust & safety context, it generally takes the form of stalking, harassment, etc., or conspiring to commit illegal acts like drug dealing, counterfeiting, or financial crimes. In general, as site owner or admin you don’t have any legal obligation to report suspected crimes (other than CSAM), but it doesn’t hurt to cultivate a good relationship with law enforcement like IC3 as the site scales. Again, it’s your playground and you set the rules, balancing free speech against standards of conduct that reflect on public perceptions of your site.

- The most likely legal issues that will arise around user conduct are either (A) that someone will threaten to sue your site based on criminal or tortious behavior of someone they met through it (e.g., “You should pay me back the $1,500 I sent to a Nigerian scammer I met on your site”), or (B) you will be contacted by lawyers or investigators with a subpoena or other records request related to the commission of a crime or legal dispute. For (A), the best defense is a well-crafted TOU that makes it clear in no uncertain terms that the site bears no responsibility for interactions among individual users. (See eHarmony’s TOU for a good example of this.) (B) is a subject for another whole article, but it’s important to respond and comply promptly with requests from law enforcement investigators in particular to freeze accounts or preserve records, and consult a qualified lawyer with any questions. It’s equally important to respect federal privacy law governing these records (the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, or ECPA), which is relatively complex and tricky to comply with. If you just turn everything over upon request, you risk violating the law; regardless of what your Privacy Policy says, you still need to comply with ECPA.

I hope you find this to be a helpful overview. Take some time to click through the various links above; there are many valuable resources available online for those seeking to master the panoply of legal, privacy, trust & safety, fraud, abuse, security and risk issues that come with the mass migration of the full range of human behavior online over the past few years. Please feel free to add issues or links to other resources you’ve found helpful in the comments.