Amid the remembrance of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, much was made of the voluminous 9/11 Commission report, which described in excruciating detail countless ways in which the United States homeland security and emergency response infrastructure failed to respond adequately to a disaster of unprecedented proportions. The “system” as it existed at the time broke down, with every point of failure costing innocent lives. The lesson of the report was clear: Preparation is everything when disaster strikes, and we as a nation were caught woefully unprepared to deal with a large-scale terrorist attack.

This principle is no less true of businesses than government agencies; particularly in the decade following 9/11, large corporations have made it a priority to invest considerable resources in disaster recovery plans, crisis management manuals, business interruption insurance and so forth.

This principle is no less true of businesses than government agencies; particularly in the decade following 9/11, large corporations have made it a priority to invest considerable resources in disaster recovery plans, crisis management manuals, business interruption insurance and so forth.

There are many kinds of business crises beyond the natural disasters and acts of terrorism that come to mind. Consider the far less serious, but still newsworthy, disaster that befell “sharing economy” growth company Airbnb this summer, which suggested its lack of familiarity with basic crisis management for consumer Internet companies that has long been part of the standard skill set of online marketplaces like eBay at scale.

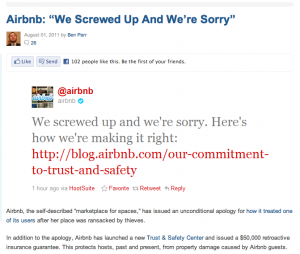

A darling of the tech startup community, reportedly valued at more than $1 billion with investors including Greylock Partners, Sequoia Capital and Andreessen Horowitz. Airbnb is an online “marketplace of spaces” that facilitates short-term rental of properties such as members’ homes or apartments. The incident, involving a woman “EJ” whose apartment was ransacked by short-term tenants who booked a stay through Airbnb, was promptly christened “Ransackgate.” The company was savaged by critics for its initial mishandling of the incident; reportedly, she got little response or assistance until she published a blog post on the subject. Social media being what it is, the post went viral and became a serious embarrassment to the company. (As an aside, I couldn’t resist calling the company “AirbnbB&E” after that—look it up.) Even then, some of Airbnb’s responses appeared to prioritize silencing the victim over accepting responsibility and resolving to do better.

How could such a well-regarded, highly successful startup be so inept in its response to an entirely foreseeable customer risk/abuse incident that was guaranteed to happen sooner or later? The answer, I believe, lies in the “echo chamber” nature of Silicon Valley, early adopters, the startup community and the tech business press. Much has been written about the cooperative nature of Valley culture, and Airbnb itself was an outgrowth of the idealistic “couch surfing” movement.

As with almost any online community, the well-meaning early adopters arrive first, and if all goes well, a culture of respect evolves (together with some snark and skepticism) that keeps behavior within relatively civilized boundaries. The trouble comes when a site becomes wildly successful, going from 1,000 closed beta members to 100,000 or 1,000,000 users.  As it grows, any service will come to resemble a diverse cross-section of the general population, with the full range of human

As it grows, any service will come to resemble a diverse cross-section of the general population, with the full range of human conduct misconduct represented. I wrote about this phenomenon in a previous Techlexica post, “If You Build It They Will Abuse It,” which bears revisiting in the wake of Ransackgate.

Why wasn’t Airbnb better equipped to respond swiftly and effectively to the incident? The primary answer, in my view, lies in the vastly divergent cultures of startups vs. established businesses. (Growth-stage companies like Airbnb inhabit the middle.) A startup is in the business of creating value from nothing – or, as Steve Blank describes it, “searching for a repeatable and scalable business model.” Large companies focus on protecting and expanding upon their existing successful business. A startup that has found product-market fit needs to transition quickly into that category, with operational excellence taking precedence over bursts of creative brilliance, because it has much to lose. The very best growth companies, such as Facebook, have been able to make this transition gracefully even without changing CEOs.

We lawyers are often rightly criticized for being excessively conservative and risk averse in pointing out everything that could go wrong. In the startup world, seeking to eliminate all risk is a hallmark of big company or big firm lawyers who “don’t get it.” When speed of execution and efficiency are paramount, the eternal grind of that style of lawyering is excruciating. Yet when it comes to risk management of user communities – content, community or commerce – failure to be looking around the curve ahead can result in pretty ugly crashes.

As it gains traction, every emerging social platform or online marketplace should pause at some point and take stock of risk and abuse issues, viewed as broadly as possible. It doesn’t necessarily mean hiring an expensive consultant (or seasoned Internet lawyer delivering exceptional value) with deep expertise in the area, but applying a mindset of pessimism and paranoia is helpful for purposes of this thought exercise.

Essentially, get inside the bad guy’s head. Here are some concrete recommendations for :

- Make a list of the most obvious ways in which someone could abuse the service – either with a specific objective in mind (e.g., Nigerian money transfer scam) or out of simple malice or mischief.

- Compare notes with the rest of the team, and with external experts if possible, to see what you might be missing. Sometimes the elephant is right there in the room with you.

- Recognize that the nature of the user base will change over time, and you will become a victim of your own success. Resign yourself to the notion that almost every bad thing you can think of will occur sooner or later if the service scales to the point of hundreds of thousands or millions of users. This is one time the entrepreneur’s unflagging optimism is not helpful, and is actually downright counterproductive.

- Create a feedback loop between users reporting misconduct, community managers or moderators, and senior management to stay abreast of abuse issues as they grow and morph over time.

- Empower users to spot and report issues of all kinds. The greatest strength of consumer Internet businesses is the sheer quantity of information that can be collected, either using analytics or through voluntary reporting by users who genuinely care about the community. Consider “deputizing” some of them with limited administrator powers. Perhaps most importantly, listen.

- Crucially, prepare some kind of crisis management plan to keep in your back pocket ahead of time. Speed of response can be critical when a PR disaster like “Ransackgate” strikes. If nothing else, determine who is on the core team with clear authority to respond to any ugly abuse incidents. Most companies caught flat-footed do one of two things: Say too much or too little. Too little usually results from well-intentioned legal advice “not to admit anything” in the event of litigation. Often a company will lose more as a result of reputational damage than it would spend having to defend or settle a lawsuit. Every bad thing you can think of will occur sooner or later if the service scales to the point of millions of users. This is one time entrepreneurs’ unflagging optimism is unhelpful and actually downright counterproductive.

- In the age of social media, word of this kind of incident travels lightning fast. With a prompt, helpful response, that can be turned to your advantage. Take a look at Better Business Bureau complaints and notice how many incidents are ultimately resolved to the customer’s satisfaction. That’s generally a business’s attempt to preserve its good BBB rating. Any business with a large number of customers will have some who are dissatisfied; handling them in the right way can turn them from vocal critics who damage your brand to some of its most ardent cheerleaders.

- Plan more specific responses to the single most likely (or better yet, top 3 or top 5) kind of abuse or fraud incidents based on the unique nature of your business. Large companies sometimes sketch these out in hundred-page disaster manuals. That’s overkill for a startup with limited resources, but recognizing the need to come out with an immediate statement and involve the right people is a big head start.

- Tone is everything. Showing empathy, admitting that nobody is perfect, expressing an earnest desire to make things right – and actually taking care of the squeaky wheel to his or her satisfaction – speaks volumes about a company and how much it cares about its customers.

- Know where to draw boundaries. No company will make 100% of its customers happy 100% of the time. Develop a think skin regarding (a) garden-variety commercial disputes, which are devoid of news value and therefore won’t have “legs” in the media, and (b) genuine nutcases, of which there will be plenty.

To its credit, Airbnb came out with a long list of improvements in the wake of “Ransackgate,” but only after sustaining serious damage to its reputation that undermined confidence in its sharing-economy, trust- and feedback-based business model. More than fifteen years into the consumer Internet revolution, there is no excuse for not foreseeing and preparing for the kind of incident that major players in online dating, e-commerce and similar businesses have been dealing with since the mid-1990s. Financial, legal and reputational consequences await those who are reactive rather than proactive in crisis management for consumer Internet companies—and competitors will take advantage of each misstep. (As Michael Arrington wrote in TechCrunch, in Airbnb’s case, “The hotel lobbyists couldn’t ask for anything more.”)

Connect with Antone Johnson on Bluesky Social or Mastodon.