Having taken stock of the main legal documents and actions involved in forming and operating a new venture, let’s crack open the “case” (disregarding the warnings about voiding your warranty) and examine a few of the steps, documents and key decisions to be made in getting a new startup ready for business. Foremost among considerations, beginning with naming, is the broad landscape of intellectual property for new startups.

Most startup lawyers have checklists (at least in their heads) and will interview a new client to gather a wide range of relevant information before moving forward with business entity formation, documentation and so forth. Sometimes this is done in the form of a questionnaire. I prefer a hybrid approach because founders come from all kinds of backgrounds, and while some may have a strong point of view on every question in the startup questionnaire, others want or need more guidance in answering the questions that call for decisions to be made.

I. What’s in a Name?

Let’s start with your name. Most new startups have a name in mind, or have even taken various steps to secure rights to the name, but some are on the fence or still developing a brand name when we first meet. Don’t let naming issues stop you from incorporating and taking care of other legal housekeeping; a corporate name change is a simple matter that can be handled inexpensively, at least in business-friendly states like Delaware.

It bears mentioning that a startup’s corporate name doesn’t necessarily have to be identical or even similar to the product or domain name. Historically, most bricks-and-mortar businesses were named after their founders, and large corporations often have a publicly traded parent company that holds all of the stock in many operating units that have familiar or famous names (e.g., AMR as holding company for American Airlines). Even technology companies followed this tradition in the early years; for every IBM, Intel or Microsoft there was a Fairchild, Hewlett-Packard or Wang.

[su_pullquote]For a startup that becomes a successful growth company, the name becomes its core identity as it “crosses the chasm” to mainstream adoption.[/su_pullquote]Nevertheless, in the era of Internet and mobile services, in which companies tend to have a very direct relationship with end users, most founders want to name the company after the first (or only) product or service around which the startup is built. Building brand awareness is a key challenge for most startups. For a startup that becomes a successful growth company, the name becomes its core identity as it “crosses the chasm” to mainstream adoption. This comes in handy for things like business press coverage, corporate PR, and ticker symbol if and when the company goes public. It also has its downsides if the primary product or service is such a powerful brand that consumers wrongly associate the corporate name with only that product. For example, during my tenure at eHarmony, Inc., we gave considerable thought to branding issues as the company branched out from its flagship eHarmony online dating service, adding other services under names like Compatible Partners and Jazzed.

Assuming the company will be named after the product, the most common step founders have taken before we meet is to acquire one or more domain names. As the consumer Internet has matured, it can be a major victory to acquire any decent-sounding name in the core .com top-level domain. Nevertheless, many startups launch under a different (less expensive) domain such as .co, .ly or .to, deferring the expense of acquiring the coveted .com name until after a funding event.

It can be a painful and expensive mistake to acquire a highly valuable domain name intending to use it as the foundation for your startup’s new brand, only to discover that there are show-stopping legal conflicts. In fact, some domains for which brokers would charge a fortune are virtually worthless, as I’ll explain below.

To cut to the chase, for the typical startup we work with from inception, there are four levels of name clearance needed to ensure smooth sailing:

- The corporate name is available in Delaware (or other state of incorporation);

- The corporate name is available in California (or other state in which the company’s operations will be based)

- One or more acceptable domain names are available that incorporate the brand name; and

- There are no serious trademark conflicts with existing brands.

Most entrepreneurs focus on #3, and perhaps are also aware of the ability to search state business entity databases online (as with Delaware or California). Perhaps they even know about the US Trademark Office online service called TESS that allows anyone to search the federal trademark registry for free. In my experience, the most common traps for the unwary are:

Most entrepreneurs focus on #3, and perhaps are also aware of the ability to search state business entity databases online (as with Delaware or California). Perhaps they even know about the US Trademark Office online service called TESS that allows anyone to search the federal trademark registry for free. In my experience, the most common traps for the unwary are:

- Nearly identical corporate names already registered in the relevant state(s)

- Identical names registered in other states or countries, for Internet businesses and others that cross boundaries

- Confusingly similar domain names that will divert valuable traffic if the service scales

- Perhaps most importantly, trademarks – whether or not registered – already in existence as of the date the startup begins doing business.

My trademark lawyer colleagues could write several articles on this last point alone. Here is my shot at an abridged, TL;DR version:

- [su_pullquote]A USPTO trademark database search won’t reveal that company in Tajikistan that started selling an Android app six months ago under the exact same name you want to use for a similar iPhone app that hasn’t launched yet[/su_pullquote] Trademark is a noun, not a verb. The legal action is called registering a mark. This can be done at the state, federal or international level (country by country). Territory matters, as does class of goods or services covered.

- In the US, actual use of a name, phrase, logo, tagline, etc. as a trademark in commerce is usually enough to begin accruing common-law trademark rights, regardless of whether the company registers the mark. (Things work differently in many other countries.)

- That said, even if they were first to use a particular name, most businesses of any scale want to protect their brands by filing an application to register it as a federal trademark in the US, at a minimum, and possibly in other countries.

- You don’t know what the trademark registry doesn’t tell you – i.e., even if you diligently search the TESS database, it won’t reveal that company in Tajikistan that started selling an Android app six months ago under the exact same name you want to use for a similar iPhone app that hasn’t launched yet – which may not ever register the TM in the US, but may have common-law rights to the name.

- Similar-looking or –sounding marks are easily missed in a search: Hyphens or other punctuation, deliberate misspellings, “C” vs. “K,” etc.

- Trademark law is notoriously subjective, and reasonable minds can differ about whether two names are confusingly similar, or whether two companies’ products are similar enough that having the same name is likely to create confusion in consumers, and so forth.

Alert readers may wonder why I’m discussing offense (enforcing your company’s exclusive useof a name) together with defense (determining the ability to use a name at allwithout getting sued). Trademark law is one area in which the best defense truly is a good offense. The process of searching for and registering your own trademark flushes out conflicting names, and may even reveal competitors you didn’t know existed, along with other benefits.

II. Nuts and Bolts

So you’ve chosen a name for your startup, product, or both. Having covered all the bases to ensure that your corporate name is available, the domain name can be acquired, and the name doesn’t infringe any existing trademarks, now is a good time to look at the categories of intellectual property for new startups.

Most traditional, bricks-and-mortar businesses have substantial, often enormous hard assets, such as raw materials and supplies, work-in-process, inventory, manufacturing equipment, real estate and more, as well as armies of employees. Tech startups are at the other extreme. The gulf has widened with the proliferation of social Internet / user-generated content and mobile application startups. (Instagram is a textbook example.) It’s possible to have a company with literally millions of customers (users) that employs only a handful of people, working in a small rented office, with hardware and software costing in the tens of thousands rather than millions of dollars.

Most traditional, bricks-and-mortar businesses have substantial, often enormous hard assets, such as raw materials and supplies, work-in-process, inventory, manufacturing equipment, real estate and more, as well as armies of employees. Tech startups are at the other extreme. The gulf has widened with the proliferation of social Internet / user-generated content and mobile application startups. (Instagram is a textbook example.) It’s possible to have a company with literally millions of customers (users) that employs only a handful of people, working in a small rented office, with hardware and software costing in the tens of thousands rather than millions of dollars.

Most of our early-stage startup clients fit this description. Even in purely online businesses, to scale from zero to millions of users:

- in the 1990s, an Internet company might have had to build a whole data center from scratch (as we did at Excite@Home — twice — only to ultimately shut them down in bankruptcy).

- In the 2000s, the company might rent space at a colocation facility; buy, install, provision and maintain its own servers, storage and networking equipment (as we did at MySpace, putting several new servers online per day); and enter into a series of contracts for ever-changing amounts of bandwidth.

- Today, it can sign one deal with a cloud service provider such as Amazon Web Services(AWS) to replace all of the above.

After eliminating all of these types of assets, what remains? Intellectual property (IP). Second in importance only to talented people, IP in all its forms is the key asset comprising most of the value of any tech startup. Nevertheless, even industry veterans are often fuzzy on the definitions and boundaries between different types of IP and the ways they can be protected and exploited. Hence this “Cliff’s Notes” refresher, to be followed by a discussion of why it matters.

- Trademarks, which we touched on last week, are brand and product names, graphic logos, slogans, taglines, and other indicators of origin of the goods or services in question. In the Internet era, trademarks and domain names are closely interrelated, and both can be or become extremely valuable. (What do you suppose the market value would be of the trademark “Facebook,” its lowercase “f” symbol, or the Facebook.com domain?)

- Copyright is the right to control reproduction and distribution of original works of authorship fixed in tangible forms of expression. Every original work is automatically copyrighted under US law upon creation, whether or not registered (although there can be significant benefits to registration). This includes website content and software code as well as the more obvious examples in media and publishing.

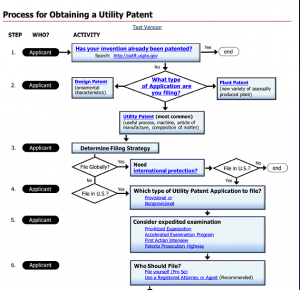

- Patents are property rights granted by the government to exclude all others from making, using, selling or importing anything that uses or incorporates the patented invention (usually described as a new, useful and non-obvious method or process, described in enough detail that it can be reduced to practice). Patents are highly technical, hard to get, and the process is slow and expensive, but for those who succeed, the payoff is a 20-year government-sanctioned monopoly over the patented technology.

- Trade secrets are everything else that would be considered confidential or proprietary. Trade secrets in the US are governed by state law, which can vary, but in general, can include anything from clever ways of solving technical or business problems to formulas, algorithms, internal pricing or financial data, or just about any other valuable business information, provided that it’s treated as confidential by the company.

Each of these categories is a deep subject that can be explored in a future post. For now, focusing on the early stages of getting a startup off the ground, it’s worth understanding the basics of the IP assets that are dumped into the empty receptacle of a newly incorporated business entity. If all goes well, the value of those assets will grow geometrically over time to eventually be worth millions or even billions.

Here are a few key questions and observations that I offer to any newly incorporating startup:

- Who are the founders? Has anyone already left the picture? Were outside advisors, contractors or consultants involved? Every person who has touched the new business in any way has a potential claim to related IP rights. This may never amount to much if the business fails, but for a highly successful growth company, “minor” claims have a way of coming back at the worst time with more zeros.

- [su_pullquote]Second in importance only to talented people, IP in all its forms is the key asset comprising most of the value of any tech startup[/su_pullquote] One common mistake is to equate “IP” with “code”or other technical contributions. The concept of intellectual property for new startups should be viewed expansively: The business is new, the team is small, branding/UI/UX is in flux, and as a matter of practicality, anyone can have input on nearly anything, from business and marketing plans to product design decisions. As an extreme example, that graphic designer or photographer who was paid as an independent contractor to create an image for the website may have also offered some input on other aspects of the user experience after reviewing a demo or mockup. If that’s the case, without a proper contract in place, it wouldn’t necessarily be sufficient to take down the picture. Get a contract, if only a simple one-pager, stating that everything the contractor produces on the company’s dime is the property of the startup. This is often referred to in the creative community as a “work-for-hire agreement.”

- Who on the team, if anyone, is moonlighting, and how closely related is their work to the startup’s business and technology? In general, if a startup team member is employed elsewhere, any work on the startup should be done on his or her own time, using entirely separate equipment and none of the employer’s assets (IP or physical) whatsoever. Laws regarding IP assignments vary by state and this is an area that should be reviewed carefully with legal counsel if there are any concerns.

How does all of this translate into typical legal documents evidencing intellectual property for new startups? Apart from registration issues, which are beyond the scope of this post, there are three main tools commonly used:

- Non-disclosure Agreements (NDAs or confidentiality agreements) are used (some would say overused) for many reasons, but one of them is to maintain trade secret status when sharing information with external parties. Proprietary information can lose trade secret protection if the company doesn’t make reasonable efforts to treat it as such.

- Stock Purchase Agreements with founders require them to assign all IP rights they may have already created or acquired (for example, code written or domain names purchased by the individual) to the corporation in exchange for their shares of founders’ stock.

- IP Assignment Agreements with founders, employees and consultants clarify ownership of all IP created going forward (the work-for-hire concept described above) and cover many other bases related to preservation of IP rights going forward. These often go by a long-winded title such as “Confidential Information and Invention Assignment Agreement” (CIIAA) or “Employee Proprietary Information and Inventions Agreement” (PIIA).

- [su_pullquote]Every person who has touched the new business in any way has a potential claim to related IP rights[/su_pullquote] Apart from all the other benefits of good corporate hygiene and risk management, handling these IP issues carefully from inception can go a long way to allay the concerns investors or their counsel may have in doing due diligence.

III. Contributing Value

I’d like to take a step back and discuss the significance of intellectual property for new startups as a component of the overall value that founders intend to create as they grow the company. The questions that arise most with respect to any category of IP at the earliest stages include:

- How will this affect our chances of getting funded on favorable terms?

- What kind of advantage will this create vs. our competitors? Barriers to entry?

- How much is it worth investing in cultivating and enforcing an IP portfolio?

- Are there any rights the company risks losing if it does nothing to preserve them now?

- What kind of risk do we run of being put out of business by others’ IP rights?

Later stage companies have some additional concerns:

- What favorable impact could IP have for PR, marketing and investor relations purposes, or as an attraction to potential acquirors?

- To what extent are we able and willing to assert proprietary IP (usually patents) as aweapon against competitors?

- To what extent are we vulnerable to attack from competitors or patent trolls? Is there anything we can do about it?

- How much is it worth investing in international IP protection, if at all?

- What is the risk-benefit calculus for developing and protecting proprietary technologies vs. buying or licensing them (“build vs. buy”)?

- How much risk do IP issues in the aggregate pose to our business?

- To what extent might proprietary IP rights be undermined by antitrust laws?

Nearly every point above is subjective, varies from company to company, and at its core is more of a business judgment than a pure legal question. For this reason, among others, tech startups are well served by engaging a good IP lawyer early in the game to help develop overall strategy and call the plays rather than just execute them.

Starting with the first point, in general, IP assets of demonstrable value that are relevant to the startup’s business can only help when pitching investors. This could include anything from a clever domain name in the coveted .com TLD to issued patents or patent applications that could serve as barriers to entry for potential competitors. The only exceptions that come to mind are if the IP seems likely to provoke costly litigation, costs too much to develop, or taints the startup with some kind of ties to other ventures or people that give it a checkered past. For these reasons, it’s helpful to do things right the first time and ensure that all relevant IP is properly disclosed and assigned to the corporation, as discussed above.

Defensible competitive advantage, often called a “moat”, is an area in which many investors are justifiably skeptical. Patents are the only way to legally exclude others from doing something similar, and then only if the method or system used infringes the claims of the patent. (It’s often possible to “design around” a patent to operate a business that achieves similar results in different ways.) As we’ve discussed, obtaining a patent can be a slow, costly and difficult process.

Most investors will assume that if the business plan is solid and a large market opportunity exists, there will be vigorous competition from other players. In general, IP protection will do nothing to prevent others from independently developing something similar, copying the overall business model, targeting similar customers or end users, and perhaps even mimicking the product’s look and feel. The most effective response is to beat the pants off the competitionthrough brilliant product design, superior technology, clever marketing, strategic partnerships, swift execution, and so forth. (Easier said than done!) This is not to suggest there is no legal recourse whatsoever, though. The quicker the startup establishes a strong brand identity that “sells itself” through word-of-mouth and social media, earning goodwill in its name, the sooner it can effectively chase away knockoffs that try to use confusingly similar names, logos, or domain names. If the startup develops a uniquely effective or efficient system to solve a business or technical problem, regardless of whether it ever seeks patent protection, that proprietary method can and should be treated as a trade secret.

The amount of investment in IP rights and registrations in any direct sense is generally small for early stage startups. Measured as a discrete line item in a budget, it might be near zero. But given the expansive definition of IP discussed previously, in fact almost everything done by most members of the founding team at a startup on a daily basis involves the creation of one kind of IP or another. Here are just a few examples:

- Creating and revising a business plan (copyright, trade secret)

- Creating product mock-ups, wireframes, etc. (trade secret)

- Writing, debugging, testing and deploying code and scripts of all kinds (copyright, trade secret)

- Developing Web content (both the design and underlying code) (copyright, trademark)

- Building and populating databases of user-supplied information and content (copyright)

- Designing and producing marketing and PR materials (copyright, trademark)

- Financial, technical and operational plans and forecasts of all kinds (trade secret)

- Sales and marketing plans, lists of prospects, supplier and subcontractor relationships, pricing data, media buying plans and strategies, etc. (trade secret)

- Internal org charts, job descriptions, titles, resumes, compensation details and direct contact information for individual employees (trade secret)

At the earliest stages, direct IP expenses might include beginning the process of registering the company’s primary brand and logo as trademarks; registering copyright in any exceptionally valuable works of authorship before they are distributed to the public; and filing provisional patent applications for any proprietary technology that seems to be unique, original, useful, and of future economic value.

This leads to the next point about “using or losing it,” which can be a concern for some types of intellectual property for new startups in some countries. In the United States, a patent application must be filed no later than one year from the date the invention is first described in a publication, used publicly, or placed on sale; otherwise, any right to a patent will be lost.  The rules are stricter in most foreign countries, where the inventor must file a patent application on the date of public use or disclosure in order to preserve patent rights. In practice, this leads many U.S. startups to ignore foreign patent protection in the early stages, only to learn that they’ve lost the opportunity altogether if they try to pursue foreign patents later when better funded. (By 2013, the U.S. will transition to a similar system as a result of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011.) Such a “first-to-file” system also applies for trademarks in most countries outside the United States, setting the stage for ugly disputes involving companies that invest heavily in building their brands domestically while deferring international trademark protection.

The rules are stricter in most foreign countries, where the inventor must file a patent application on the date of public use or disclosure in order to preserve patent rights. In practice, this leads many U.S. startups to ignore foreign patent protection in the early stages, only to learn that they’ve lost the opportunity altogether if they try to pursue foreign patents later when better funded. (By 2013, the U.S. will transition to a similar system as a result of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011.) Such a “first-to-file” system also applies for trademarks in most countries outside the United States, setting the stage for ugly disputes involving companies that invest heavily in building their brands domestically while deferring international trademark protection.

The possibility of being put out of business by a ruinous patent suit brought by a large corporation with deep pockets understandably creates anxiety among entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, experience has shown this to be primarily a later-stage company problem. Paul Graham explains:

We tell the startups we fund not to worry about infringing patents, becausestartups rarely get sued for patent infringement. There are only two reasons someone might sue you: for money, or to prevent you from competing with them. Startups are too poor to be worth suing for money. And . . . they don’t get sued by other startups because (a) patent suits are an expensive distraction, and (b) since the other startups are as young as they are, their patents probably haven’t issued yet. [Large companies] win by locking competitors out of their sales channels. If you do manage to threaten them, they’re more likely to buy you than sue you.

[su_pullquote]Almost everything done by most members of the founding team at a startup on a daily basis involves the creation of one kind of IP or another[/su_pullquote] As in the notorious Blackberry case a few years ago, the more successful the business, the more the company has to lose, and the more it will pay to settle and obtain a license to the patented technology ($612 million in RIM’s case to avoid a shutdown of the entire Blackberry network).

IV. More on Domains and Trademarks

One of the best values a young entrepreneur can absorb early on is the value of learning from mistakes, both your own and those of others. I’m constantly amazed at the extent to which experienced entrepreneurs and angels are willing to share their accumulated knowledge and wisdom, including some painful battle scars, with others. This bedrock of Silicon Valley culture is a prerequisite for the whole phenomenon of venture accelerators. It’s the radical opposite of the prevailing culture in established or contracting industries, where all things proprietary or innovative are jealously guarded and information is shared on a “need-to-know” basis. This spirit of “coopetition” is one of the things I truly love about the startup community.

In the same vein, lawyers learn from mistakes, both strategic and tactical. One reason business lawyers tend to specialize is that it’s more practical to amass knowledge of pitfalls to avoid, and things that can go awry, in a given area of focus. No human being can be equally knowledgeable about all things. This is why experienced General Counsel know that the most important executive decision to be made at the outset of any new matter is whom to ask, or which firm to engage, to handle it.

In emerging companies and venture capital (ECVC) practice, we tend to be subject matter generalists but industry specialists. I will freely admit that I’m not the lawyer to consult if your apparel business is facing a trademark dispute with counterfeiters in Vietnam, but if you’re starting a consumer Internet business, the road from private beta to millions of registered users is strewn with corpses that I’m happy to identify. The kind of legal advice I find most personally rewarding helps new players steer clear of foreseeable disputes, avoid overinvesting in legal work to mitigate risks that are more theoretical than real, and invest wisely when the best defense is a good offense.

In an earlier section, I discussed some basic considerations in choosing a name for a new startup. As you may recall, there are multiple layers of name rights that can come into play, including trademarks, domain names and corporate names. Things get interesting when a company goes international, becomes a household name, or simply gets popular enough to attract a lot of traffic — which then attracts the squatters looking to monetize that traffic. It’s an area in which investing early in more protection rather than less, optimistically planning for future growth, can pay dividends down the line. Nevertheless, when a company is young and strapped for cash, filing trademark applications all over the world and defensively registering every potentially confusing domain name variant in every new top-level domain (TLD) to come along worldwide is simply not a realistic strategy in a world of competing priorities.

Most startups begin life as single-product, single-market businesses. Let’s assume for discussion’s sake that it’s a US-based company using the same name for the corporation as for the product (e.g., MySpace, Inc.). As we’ve discussed, it helps to start out as clean as possible with a brand name that’s available as a corporation, a trademark, and a domain name, with no existing conflicts. The more “arbitrary or fanciful” the name (e.g., Yahoo!, Google), the less likely there is to be any trademark or domain conflict from inception. Generic or descriptive names start out in crowded territory to begin with, are harder to protect, and face stiff competition from domainers for similar-sounding names (Widgets.com vs. MyWidgets.com, Widget.com, WidgetCo.com, and so on).

Of course the main disadvantage of going with a name like Etsy or Zynga is that it starts out meaningless to the consumer. The opposite extreme (e.g. About.me or Buy.com) requires no explanation but is a nightmare to obtain and protect. My favorites are suggestive names like Twitter, LinkedIn or YouTube that strike a good balance, being highly suggestive yet not merely descriptive or generic. Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that even generic or descriptive names can become imbued with what trademark lawyers call “secondary meaning” — that is, even if the name “Windows” is descriptive, after selling hundreds of millions of copies, its use in a computing context can only reasonably be associated with Microsoft Corporation.

So you’ve got a startup with a clever, well-thought-out name, incorporated and acquired the domain name under the most valuable .com TLD. What next?

Trademarks

- File an application to register the trademark with the US Trademark Office. Ideally you’ve already engaged a trademark lawyer to do a search to make sure someone else hasn’t already registered the name you have your heart set on, or something confusingly similar. (Sorry, you probably can’t get away with MeTube or Googol.) Regardless, as soon as the company starts investing real money in building brand awareness, it would be foolish not to protect that investment with U.S. federal trademark registration at a minimum.

- The process can take a couple years (usually less) but doesn’t require extensive legal work unless you run into a head-on conflict with another company that is willing to expend resources to oppose your use of the name. In the mean time, the company can begin accruing common-law trademark rights (in the U.S.) by actually using the name in commerce, “as a trademark” (meaning a designation of origin). It helps to use the TM symbol at least in the first place the name appears in any given page or document.

- International trademark registration is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that trademark law is country-by-country (with a few exceptions such as the European Union). For domain name enforcement purposes, the most urgent priority will usually be to get a trademark registration here in the U.S.

Domain Names

- [su_pullquote]The more your business scales, the more the price of everything will go up[/su_pullquote] There’s no reason to hold off acquiring domain names that are available for registration or sale at a reasonable price. The good news is that domain name registrations are cheap. The bad news is also that domain name registrations are cheap! Domainers make a living buying low and selling high, in much the same way as real estate speculators. If your name is generic or descriptive, it’s virtually certain that the domain name is already taken under the most valuable .com TLD. Many times it will be “parked” at a site such as Sedo.com and listed as available for sale. In reality, everything is negotiable provided you can actually get in touch with the domain owner.

- It should be evident from this discussion that the best way to avoid overpaying for every conceivable variation of your brand name is to register them all first, paying the minimum price (“defensive registration”). Once the business gains traction and appears on speculators’ radar screens, in all likelihood they will grab every close variant they can find, including typos and misspellings (eharmoney.com), punctuation variants (e-harmony.com), and so forth.

- What’s wrong with this picture? Simple math. Unfortunately, even if domains only cost $20 apiece, by changing a few characters it’s possible to come up with thousands of variants of a domain name. This is particularly true with every new TLD that opens up. (The introduction of .xxx is a good example. That TLD is limited to sites in the adult entertainment industry as well as brand owners that wish to register defensively for obvious reasons.)

- The more your business scales, the more the price of everything will go up. At a famous brand, high traffic site, even a small percentage of mistyped URLs will net a decent number of hits for an enterprising domain squatter. That makes it more worth their while to register an ever-widening circle of similar domains in the hope of getting a payoff.

The Carrot And The Stick

- Like an emerging military power, the bigger you become, the more skirmishes are likely to occur at your borders. As problems go, these are good ones to have, considering they come with scale and rapid growth. Nevertheless, it helps to be prepared. Fundamentally, there are three ways to obtain a domain name held by another party: Negotiate to buy it, file a lawsuit, or pursue arbitration under the ICANN rules known as the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP).

- Practically speaking, nothing beats simply negotiating to buy the domain for a modest price. Although it may seem unfair to pay anything to someone who is taking advantage of your success, legal proceedings are expensive, time-consuming and stressful distractions from building your business. In addition, a good settlement agreement will buy you some comfort in the future (e.g., an agreement not to turn around and squat a dozen other variants of your primary domain name).

- Litigation can be incredibly expensive. Expect to pay six figures in legal fees for any trademark infringement lawsuit, or even more. It’s rarely worth it for any startup.

- UDRP is often the only practical alternative for a company that is intent on reclaiming a domain from a party who is unwilling to sell it or insists on an unreasonable price. Without getting into the gory details (which can be found here), it gives the brand owner an opportunity to make a case for abusive registration — i.e., that the domain name is confusingly similar or identical to your company’s trademark and that the current domain owner has no legitimate purpose for registering it. This is a key reason why having a registered trademark is important. UDRP is a “stick” to use against uncooperative squatters that is far less expensive than litigation. The Chilling Effects Clearinghouse maintains an excellent FAQ with more information on the process.

A successful business in the Internet age will have to wage an ongoing war against domain name squatters, fought one battle at a time. There is no practical way to prevent it altogether, but an up-front investment in trademark registration and the most obvious candidates for cybersquatting and typosquatting can save a lot of headache and expense if your startup turns out to be the “next big thing.”

This article was compiled from a series of posts at Gust Blog.