Only a few days later, I’m needing to break my own “Top 10” rule and add two more valuable resources, making it an even dozen. For founders who want to get into the nitty-gritty details of venture capital and angel financing documents, there are two online resources from leading Silicon Valley law firms that are well worth your time.

I offer these links notwithstanding my own strong belief that there is a time and a place for DIY projects; as an entrepreneur, negotiating the finer deal points of selling precious shares of equity in the fruits of your life’s labor is not like changing the oil in your car. (I’d liken it more to rebuilding the engine yourself–or at least doing a ring and valve job on a V8.) A professional who’s seen the full range of deal terms over the course of many deals for many startups can add value far beyond legal wordsmithing. Nevertheless:

- Founders are smart, independently minded and curious people;

- Selfishly (for me), an educated client needs less hand-holding and is a joy to work with;

- Selfishly (for you), the more homework you do first, the quicker the funding process can move and the less it will cost in legal fees; and

- Some brave souls will go ahead and DIY anyway (see #1), so go forth and conquer–and then call me when you’re ready to hire a lawyer for your next deal!

After that soapbox preamble, here they are:

Venture Capital Financing (VC) Term Sheet Generator

My “alma mater” law firm, Silicon Valley giant Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, has created an online VC Term Sheet Generator for venture financing deals.  It’s a comprehensive, wizard-like tool that walks founders through each of the deal terms commonly included in a VC term sheet, enabling them to fill in the blanks electronically, and generates a full document at the end in RTF format. See this example. It’s well worth spending an hour or two trying it out with various hypothetical deal terms to get a sense of the range of options for each and familiarize yourself with the legalese as it appears in a real term sheet. This tool is an outstanding resource, and looks to be the product of a ton of hard work by the team at WSGR (notably Yokum Taku, who also authors an excellent blog). They should be congratulated for making it available to the public.

It’s a comprehensive, wizard-like tool that walks founders through each of the deal terms commonly included in a VC term sheet, enabling them to fill in the blanks electronically, and generates a full document at the end in RTF format. See this example. It’s well worth spending an hour or two trying it out with various hypothetical deal terms to get a sense of the range of options for each and familiarize yourself with the legalese as it appears in a real term sheet. This tool is an outstanding resource, and looks to be the product of a ton of hard work by the team at WSGR (notably Yokum Taku, who also authors an excellent blog). They should be congratulated for making it available to the public.

One suggestion for my friends at WSGR: Why not add a link at the end of the process to share your term sheet via social media? Something like a ShareThis widget that would allow me to tweet or share on Facebook with the click of a mouse. ![]() (“I just created a Series A venture financing term sheet for my startup using the Wilson Sonsini VC Term Sheet Generator–here it is!” — or for the more bashful, in a private email link.) Obviously most founders wouldn’t want to tweet their real proposed deal terms to the entire world, but entrepreneurs and business students are a social bunch and might want to learn by discussing hypothetical examples using social media.

(“I just created a Series A venture financing term sheet for my startup using the Wilson Sonsini VC Term Sheet Generator–here it is!” — or for the more bashful, in a private email link.) Obviously most founders wouldn’t want to tweet their real proposed deal terms to the entire world, but entrepreneurs and business students are a social bunch and might want to learn by discussing hypothetical examples using social media.

Series Seed: “Open Source” Seed Round Financing Documents

Ted Wang at Fenwick & West, another legendary Silicon Valley firm (where I worked in the file room as a college kid circa 1990, and played [badly] on the firm softball team–but that’s another story), ![]() took on a more ambitious–some might say audacious–challenge by creating a set of “open source” stripped down documents intended solely for use in seed round financings, reportedly winning the approval of Andreessen Horowitz among others. This is hot off the presses and I haven’t fully digested the documents yet, but if the early stage VC community agrees to standardize on these forms (or perhaps start with them and add deal-specific riders, the way online advertisers tend to do with IAB-AAAA insertion order forms, for example), it could strip a ton of time and money out of the typical Series A deal execution process. VentureBeat writes:

took on a more ambitious–some might say audacious–challenge by creating a set of “open source” stripped down documents intended solely for use in seed round financings, reportedly winning the approval of Andreessen Horowitz among others. This is hot off the presses and I haven’t fully digested the documents yet, but if the early stage VC community agrees to standardize on these forms (or perhaps start with them and add deal-specific riders, the way online advertisers tend to do with IAB-AAAA insertion order forms, for example), it could strip a ton of time and money out of the typical Series A deal execution process. VentureBeat writes:

[Wang] first called for a streamlined early funding process in 2007, with an editorial for VentureBeat titled, “Reinventing the Series A.” The problem, he said, is that the legal hassles and costs don’t change much between a large, institutional venture round and a much smaller seed investment — but it doesn’t really make sense to spend tens of thousands of dollars on legal fees if you’re only raising $500,000.

“Startup company lawyers are under an intense pressure to keep our fees low on these deals and we find ourselves struggling meet our clients’ expectations around pricing,” Wang wrote back in 2007. “The result is that these small Series A deals have become a source of unwanted tension between us and our clients.”

There have been other attempts to improve the process, such as incubator Y Combinator’s creation of standardized legal documents for angel funding. But Wang said his approach — developed with the advice of other Fenwick & West attorneys as well as a number of investors — is “a little more radical.” Specifically, it streams down the standard contract from 100 pages to 30 pages, and cuts legal fees from the tens of thousands of dollars to around $7,000.

![]() Law is an inherently conservative business, mostly evolutionary rather than revolutionary. No doubt there will be a chorus of naysayers immediately questioning how this approach could work. I’m not the type of lawyer who reflexively puts on the skeptic hat, and I commend Ted for taking on this challenge. He’s doing what good entrepreneurs do: Spot the customer’s pain point, thoughtfully assess the situation, and create a new kind of product tailored to solve the problem. Nevertheless, I do have to ask whether it’s more realistic for lawyers to change the way business is done, or change how we work to accommodate business. After all, the client, not the lawyer, is the center of a law practice. Here is where I climb back up onto my soapbox, reminding everyone (including myself) that “where we stand depends on where we sit.”

Law is an inherently conservative business, mostly evolutionary rather than revolutionary. No doubt there will be a chorus of naysayers immediately questioning how this approach could work. I’m not the type of lawyer who reflexively puts on the skeptic hat, and I commend Ted for taking on this challenge. He’s doing what good entrepreneurs do: Spot the customer’s pain point, thoughtfully assess the situation, and create a new kind of product tailored to solve the problem. Nevertheless, I do have to ask whether it’s more realistic for lawyers to change the way business is done, or change how we work to accommodate business. After all, the client, not the lawyer, is the center of a law practice. Here is where I climb back up onto my soapbox, reminding everyone (including myself) that “where we stand depends on where we sit.”

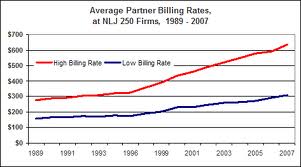

I’d to shine a spotlight on the elephant in the room here, which is cramping the rest of our lean startup team in our modest office space: High billing rates at large law firms. The basic set of deal documents for VC financing transactions has evolved only incrementally since the 1980s; the forms used today are largely identical to those that WSGR used in training sessions I attended in 1998.

What has changed? Billing rates. Junior associates at large firms today bill at the rates that partners were billing at in the late 1990’s ($300+ per hour). I started out in 1996 billing at $130/hour, at the Los Angeles office of a large Wall street firm. To get all Adam Smith on you, the fee problem that Ted identified in 2007 must not have been all that pressing five or 10 or 15 years earlier–or the market would have solved it by now. Simply put, it wasn’t as big a problem in the ’90s because large-firm billing rates were roughly half what they are today. I could write another whole post on this subject; to bottom-line it, the consensus view of current and former General Counsel like myself, as articulated by the ACC Value Challenge, is that “the value of legal services is increasingly divorced from the appropriate (and ever-rising) cost of those services.” $25K is a lot of money to a new startup, but $50K is a lot more!

What has changed? Billing rates. Junior associates at large firms today bill at the rates that partners were billing at in the late 1990’s ($300+ per hour). I started out in 1996 billing at $130/hour, at the Los Angeles office of a large Wall street firm. To get all Adam Smith on you, the fee problem that Ted identified in 2007 must not have been all that pressing five or 10 or 15 years earlier–or the market would have solved it by now. Simply put, it wasn’t as big a problem in the ’90s because large-firm billing rates were roughly half what they are today. I could write another whole post on this subject; to bottom-line it, the consensus view of current and former General Counsel like myself, as articulated by the ACC Value Challenge, is that “the value of legal services is increasingly divorced from the appropriate (and ever-rising) cost of those services.” $25K is a lot of money to a new startup, but $50K is a lot more!

I’ll finish by asserting–with admitted self-interest–that there is a third way for startups: Use experienced lawyers at (ahem) smaller, leaner law firms that boast much of the same expertise of the giant firms,  don’t have their enormous overhead, and can pass along those savings in the form of billing rates that are 30% or 40% lower for the same work. This is not just blatant self-promotion; there are many excellent lawyers these days running independent practices with more modest cost structures. The renowned (and much missed) Craig Johnson thought as much when he founded Virtual Law Partners: In a 2008 interview with The Recorder announcing the formation of VLP, Craig said, “The thing that makes it almost a slam dunk is the incredible price umbrella from the big firms. When you charge $400 an hour and have clients think it’s a bargain, how could you not succeed?”

don’t have their enormous overhead, and can pass along those savings in the form of billing rates that are 30% or 40% lower for the same work. This is not just blatant self-promotion; there are many excellent lawyers these days running independent practices with more modest cost structures. The renowned (and much missed) Craig Johnson thought as much when he founded Virtual Law Partners: In a 2008 interview with The Recorder announcing the formation of VLP, Craig said, “The thing that makes it almost a slam dunk is the incredible price umbrella from the big firms. When you charge $400 an hour and have clients think it’s a bargain, how could you not succeed?”

It would be great for entrepreneurs to be able to use simple, stripped-down forms that enable them to close a seed financing round for only $7,000 in legal fees — but law is an adversarial process, investors trust their own lawyers to look out for their own self-interest, and good lawyers want to cross all of the I’s and dot all of the T’s. This is particularly likely to be true if the company is paying the investor’s counsel’s fees as well as its own (which is usually the case). Unless the founders have atypical leverage, why would a VC voluntarily give up any deal term in the traditional package of documents — or make any substantial change to its traditional way of documenting deal — simply to save a few thousand dollars in legal fees that will likely be passed on to the startup upon closing?

To end on a positive note, I will gladly be proven wrong if the coterie of top-tier early stage VC’s decides to go along with this streamlined, “open source” approach. Again, I salute Ted Wang for trying to reinvent a process that is undeniably expensive and inefficient for startups, and look forward to hearing feedback from the venture community.